Five queer short films walk their first categories

As I mentioned last week, while I do not have more queer Palestinian short films to share with you at this time and am going back to other themes for my recs (this week’s theme is ballroom), I intend to continue using this space as a platform to express my outrage and heartbreak over Israel’s ongoing genocide on Palestinians. As of November 20, the last time before communications breakdowns kept the Gaza Ministry of Health from updating its list of casualties, 12,700 Palestinians had been killed in Gaza and almost 33,000 wounded, as well as 216 Palestinians killed in the West Bank; those numbers are undoubtedly higher now. Israel continues to bomb hospitals, refugee camps, schools, and neighborhoods all over Gaza, including in the so-called “humanitarian corridors” and areas that they have instructed Gazans to flee to, while more than sixteen Palestinian villages in the West Bank have been ethnically cleansed and forcibly displaced by settler-soldier militias. And Israel is able to do this with impunity and explicit backing from the United States and most of the western world (and a great deal of the non-western world too, including India, where my family is from).

But that doesn’t mean our efforts to demand change and accountability aren’t working. We need to hold strong for Palestine. Call your elected officials to call for a ceasefire, an end to arming Israel if that is something your country does, and freedom, self-determination, and the right to return for all Palestinians. Take part in protests and direct actions to halt the flow of weapons and military aid to Israel. Uplift the voices of Palestinians, and share your commitment to Palestinian liberation with all of your communities. Commit to the Boycott, Divest, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement. Call out lies and propaganda from genocide-deniers and enablers. We can’t stop until Palestine is free, and we owe Palestinians our hope and resistance.

I am excited to share that on the queer short films front, Queer Cinema for Palestine has announced the program for their 2023 “No Pride for Genocide” Festival, which will take run from December 2 to 10. In-person events will take place in cities across the world in Canada (London, Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver), Germany (Berlin), Korea (Seoul), Lebanon (Beirut), Netherlands (Amsterdam), and the United Kingdom (London), while films will be available for free online viewing through the Toronto Queer Film Festival website starting at the local time of the scheduled screening, and will remain on demand through the end of the festival. You can sign up for updates here.

I also want to name that in the United States, where I live, this week recalls another genocide: the genocide perpetrated by white settler colonists on the Indigenous people of Turtle Island (colonially known as North America), remembered through the National Day of Mourning, a Native American protest on the day of the colonial “holiday” Thanksgiving. For Americans like myself, instead of “celebrating” racist history, I encourage you to read Native and specifically Wampanoag perspectives on Thanksgiving, explore how to resist Thanksgiving and revive Indigenous relationships to food, learn about whose land you live on and how to pay reparations to indigenous people (for example, in Seattle, where I live, you can pay rent to the Duwamish Tribe), and celebrate and honor National Native American Heritage Month. It’s also important to note – and not just for those in the United States – that all our anti-colonial struggles are connected, and land back means land back for Native Americans, Palestinians, and all Indigenous people worldwide.

On to this week’s films! Ball and house culture has roots in Black queer and drag communities going back more than a century, but began as its own entity in New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The earliest houses were founded by Black and Latinx queer, trans, and gender nonconforming folks like Crystal and Pepper LaBeijia, Dorian Corey, Avis Pendavis, Paris Dupree, and La Duchess Wong, who were discriminated against in majority-white spaces. You can read an incredible oral history of ballroom at, appropriately, Vogue Magazine.

Ballroom has a number of key components, including a system of houses that become surrogate families for queer and trans youth; fashion, beauty, and presentation; the development of categories that each house could walk; voguing, a combination of dance, acrobatics, and posing to compete against others on the floor; and the stardom of ballroom’s legends and icons throughout its history. Ballroom is also unmistakably a space of resistance: against transphobia, against anti-Blackness and racism, against sexual violence, against the AIDS epidemic, against the oppression of sex workers, against abusive families, and more. Ballroom has an enduring presence today as an underground subculture across the world and as a part of mainstream pop culture, which brings with it the dangers of appropriation, but also makes visible a community and history that many current Black and brown queer and trans youth might not have found out about otherwise.

You can find content notes for the films at the very end of the post. Also, I include pronouns for people mentioned when I can find them explicitly stated. When I cannot, I either use what I see being used for them in articles about them, or I just use their names.

“[Vogue] is a unique expression of Black thought and Black resistance. Vogue is joy, vogue is freedom, vogue is life.”

Legendary: 30 Years of Philly Ballroom, created by Raishad Momar, Cassie Owens, and Lauren Schneiderman for The Philadelphia Inquirer, is a gorgeous documentary about the history of ballroom culture in Philadelphia, the third city to develop a ballroom scene. The docu-short includes stories from throughout the three decades, from the organization of the first Onyx Ball in 1989 by Michael Gaskins, considered the founder of the Philadelphia ballroom scene; to the perspectives of Alvernian Prestige, the “Mayor of Philadelphia Ballroom”; to remembrances of Renee Karan, the “mother of all mothers” and femme queen star who is still an icon for trans women in Philadelphia more than twenty years after her death from AIDS; to interviews and performances by newer stars. The film also impresses the importance of preservation of this history, itself becoming a piece of the living archive of Black and Latinx queer and trans culture.

Legendary: 30 Years of Philly Ballroom

“What matters most here is what I am feeling, my emotional state, so I can conquer my dreams in the ballroom.”

Blyndex: Uma Teoria Brasiliera | Blyndex: A Brazilian Theory, directed by Rodrigo Inada and Yuri Mira, is an experimental docu-short following the House of Blyndex in São Paulo. The House of Blyndex, as described in the film, is “a peripheral organization made up of Black people LBGTQIA+, and acting through the ballroom community and culture, it aims to aggregate and welcome dissident bodies to celebrate and promote the art of people on the margins of society.”

“Brazil is a country that has a lot of financial and social inequality,” the directors told NOWNESS, “and especially in the arts scene it is difficult for people that are on the outskirts of society to make it.” Since its founding in 2019, the House of Blyndex has expanded into Florianópolis and Chicago.

Blyndex: Uma Teoria Brasiliera | Blyndex: A Brazilian Theory

SATURN RISIN9, directed by Aja Pilapil (Aja Pop Films), stars performance artist Saturn Jones voguing on a bridge above train tracks. The combination of Saturn’s sharp movements, the close camera angles and cuts, and the intense music create a captivating tension and vividness. Saturn, well-known within San Francisco’s queer club scene, has talked about using dance as an outlet for his frustrations growing up gay and Black, telling SF Weekly, “It started with being angry at the fact that I was policed as a young boy by my friends and family for how I dressed and how I expressed myself. So I was just like, ‘Fuck, this is who I am.’ When I go on stage, I feel free.”

SATURN RISIN9

A Baroque Ball: Shade, directed by Frédéric Naucyzciel, features fifteen performers – fourteen from Paris’s ballroom scene, and one from Baltimore’s – vogueing to a baroque interpretation of a Bach concerto. The film itself is spare, featuring the cast dancing in and out of the camera’s fixed view in an otherwise-empty exhibition room, but the choreography, which deftly plays with the different definitions of “ballroom” featured here, brings its own glitz and glamor. Naucyzciel, whose interest in ballroom began during a fellowship in the United States when he discovered the scene in Baltimore, has since recreated the baroque ball performance onstage.

A Baroque Ball: Shade

“That’s my daughter.”

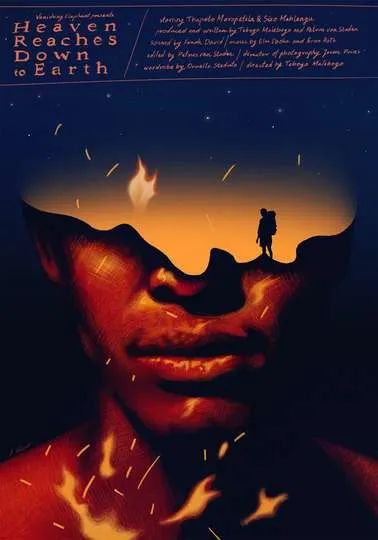

Walk For Me, written and directed by Elegance Bratton, follows Hanna (Aaliya King), a Black trans teen, through the day she makes her ballroom debut with the House of Continental. The film begins with a fraught interaction between Hanna and her stern mother Andrea (Yolonda Ross), which is then thrown into sharp relief by the way Hanna is welcomed and fussed over by her House Mother, Paris Continental (Brenda Holder), before she walks for the first time. After seeing Hanna’s phone blowing up with calls from Andrea, Paris makes a decision that will impact Hanna’s relationships with both of her mothers – hopefully for the better.

The theme of family in ballroom was key for director Elegance Bratton, who left his own bio-family in New Jersey at age sixteen and found a new home in Christopher Street in the West Village of New York City, long a haven for Black and Latinx queer folks. “I spent about four years going to balls pretty much every weekend. You go there and you see a wide range of age groups in the femme queen and trans women categories,” Bratton said in an interview with VICE. “And it’s like two or three o’clock in the morning, and [many] these kids are like 13, 14, 15 years old. And I’m just like, where are their parents at? Like where’s your mom at, your actual mom? It all started from that question.”

It was also important to Bratton to make a narrative short because in 2016, there were few narrative stories about ballroom. “The other thing is that nobody who’s from the community has ever made a story about the community,” Bratton said. “I really wanted to talk about the contemporary 21st century queer black experience as I’ve witnessed it through my skin.” The casting of Aaliya King and Brenda Holder, both Black trans stars in the ballroom scene (Brenda, whose stage name is in fact Brenda Continental, was the first to win femme queen vogue at a ball in the early 1980s), as well as the personal history that Bratton draws on, brings a verisimilitude that makes the film even more impactful and meaningful.

Walk For Me