And apparently we need to talk about it

I am pretty much eating, sleeping, and breathing the WNBA right now. I’ve been a fan of the women’s basketball in the US since 2021, which is not very long, but even in that time I’ve learned a ton and fallen in love with the game and its players. And part of the reason I’ve found women’s basketball so compelling is because Black women built this game – including many, many, Black queer women – and have used their platform not only for leadership within the sport but also to fight for social, racial, and political justice.

But looking at the current discourse about women’s basketball in the U.S., you wouldn’t know that. And in my opinion, there hasn’t been enough discussion in the media about how that discourse exemplifies misogynoir, the specific intersection of anti-Black racism and misogyny. So despite the fact that I’m not an expert and am a relatively new fan, I thought I’d write a short series with my perspectives on women’s basketball right now.

This first post is a brief history of women’s basketball through the lens of Black women’s accomplishments and leadership; the second will be unpacking misogynoir, anti-Black homophobia, and whiteness in women’s basketball, particularly in narratives around Caitlin Clark, the white player at the center of most women’s basketball media attention in the U.S. right now; the third will be on activism and fights for liberation by Black women in basketball; and the fourth, just for fun, will be spotlighting the WNBA players that I think are the most exciting to watch right now.

Women have been playing basketball almost as long as the sport has existed. After James Naismith, a physical education college instructor, invented basketball in Massachusetts in 1891 to keep his students indoors during the winter, it almost immediately caught the eye of Senda Berenson, an instructor at the nearby all-women’s Smith College. Less than a year later, the first women’s college inter-institutional game was played, and by the beginning of the 20th century, Black women were big in the sport.

1900s-1950s: The Black Fives era

During the “Black Fives era” of basketball in the first half of the twentieth century, athletic clubs, churches, newspapers, and other entities began forming women’s basketball teams. The New York Girls, created in 1910, were the first independently-run female all-Black basketball team, and were quickly joined by dozens of others. Women’s basketball also became popular at HBCUs (Historically-Black Colleges and Universities) like Bennett College for Women in North Carolina. These teams featured stars like Ora Mae Washington, considered one of the greatest female athletes of all time, who won twelve Colored Women’s Basketball World Championship titles (eleven of them back-to-back) in the 1930s and 40s.

Black women challenged assumptions that female basketball players were inferior to men, as well as that they should be dainty and frail. Chicago’s Club Store Coeds, also known as the Chocolate Coeds, were so good that other women’s teams started refusing to play them, so they started beating men’s teams instead, traveling all over the United States to do so. However, the “threat” of women’s basketball – both to men’s sports, and to femininity and heteronormativity – led educators and authorities to work to curtail the sport beginning in the 1920s. By the 1940s, many HBCUs had dropped their women’s sports programs, and the independent teams created by athletic clubs began to die out as well.

1970s-1990s: The beginning of modern women’s basketball

Women’s basketball took new form in the 1970s. The Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) was founded in 1971 to serve in parallel to the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), which at the time only governed men’s collegiate sports. The AIAW featured many basketball teams made up entirely of all Black women, including the Federal City Pantherettes, created by Bessie Stockard in 1969, which was likely the first Black women’s basketball team to reach a number one ranking nationally. HBCUs also featured many women’s basketball stars.

The passage of Title IX in 1972 created another sea change for the sport. This was a mixed blessing for Black women in college basketball: on the one hand, there were more resources and players, but on the other hand, by the early 1980s, this led to the dissolution of the AIAW and the takeover of women’s college sports by the NCAA, which meant that men gained leadership positions over women in coaching and administration of women’s college basketball.

This also led to the erasure of accomplishments by Black collegiate athletes of the 1970s. For instance, Pearl Moore still holds the all-time women’s college basketball scoring record at 4,061 points – yes, that’s more than Caitlin Clark’s record, which is 3,951, and Moore did it before three-point shots existed – but Moore did so both at the small-college level and under the AIAW, which isn’t counted by current NCAA records. Lusia Harris-Stewart, a huge star from Delta State University, was not just the only woman ever officially drafted by an NBA team (she didn’t attend the training camp, thinking they weren’t serious), but was also the first woman in the world to score in an Olympic women’s basketball tournament in 1976 – yet she is nowhere near as well-known as her Olympic teammates Pat Summitt, Nancy Lieberman, and Ann Meyers-Drysdale, all of whom are white.

The 1980s led to new highs for women’s basketball. The first Division I NCAA tournament for women’s basketball took place in 1982, with HBCU Cheyney State coming in as a number two seed and reaching the finals, where Louisiana Tech ended their 23 game win streak. In 1984, the U.S. women’s Olympic team won its first gold with a roster of Cathy La Ora Boswell, Denise Curry, Ann Donovan, Teresa Edwards, Lea Henry, Janice Lawrence Braxton, Pam McGee, Carol Menken-Schaudt, Kim Mulkey, Cindy Noble, Cheryl Miller, and Lynette Woodard, half of whom are Black. Miller and McGee were also chosen for that year’s Kodak All-America team – a selection of top collegiate players that had been running yearly since 1975 – which for the first time featured an entirely Black roster that also included Tresa Brown, Janet Harris, Annette Smith, Becky Jackson, Yolanda Laney, Janice Lawrence, Marilyn Stephens, and Joyce Walker.

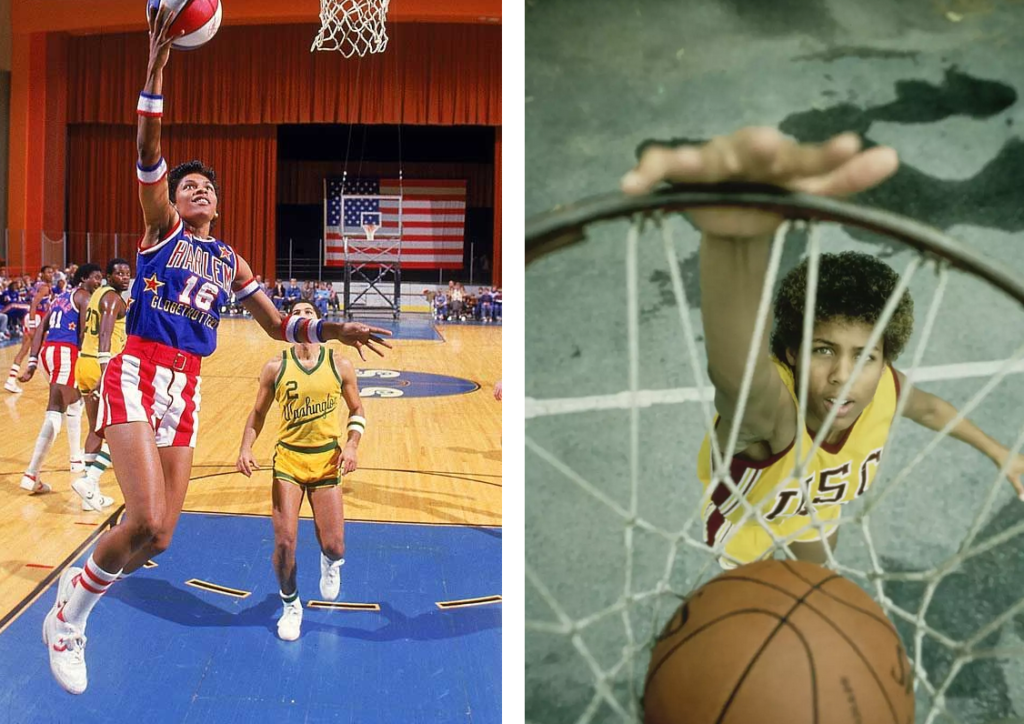

Cheryl Miller is in fact one of the greatest women’s basketball players of all time. In college at USC, she led the Trojans to a 112-20 record and two back-to-back NCAA championships in the early 1980s. She won Naismith Player of the Year three times and is still tenth all-time in NCAA scoring history and third in rebounding, averaging a double-double of 23 points and 12 rebounds per game. After college, she was drafted by the men’s United States Basketball League, but injuries in the late 1980s ended her playing career.

Another legend who grew to fame in this era was Miller’s Olympic teammate Lynette Woodard, who played college basketball at the University of Kansas, where she was a four-time All-American, averaged 26 points per game, and scored 3,649 career college points from 1978-1981 – a major-college record that would not be broken until earlier this year (and like Pearl Moore, there were no three-point shots when Woodard did it). In 1985, she became the first woman ever to play with the Harlem Globetrotters. But unlike Miller, Woodard was able to continue playing long enough that she also joined the Women’s National Basketball League (WNBA) – after the birth of another new era of women’s basketball in the US.

1990s: Women’s basketball goes pro

Despite success in the 1980s, the early 1990s brought defeats for the US women’s national basketball team at the Olympics and FIBA World Championships. As a result, a group of organizers decided to try and revive US basketball prowess and also capitalize on the growing interest in women’s college basketball – especially as still-powerhouse programs like Tennessee, Stanford, and UConn started leading – by putting together a team that would play in an year-long exhibition tour against college and international teams before competing at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta. The underlying hope was that, if successful and popular enough, this would spark the creation of a women’s professional basketball league in the US.

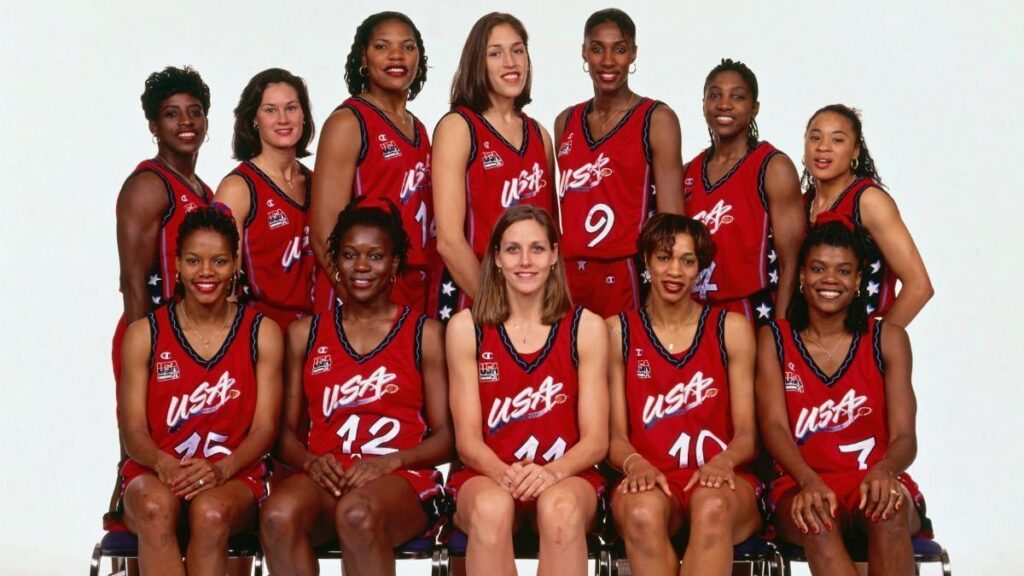

It was, in fact, successful and popular enough; the team, whose roster was 75% Black, won every single match on their 52-game tour, which took them 100,000 miles across five countries, culminating in taking home the Olympic gold. And the team’s success led to the founding of not one but two women’s pro leagues: the American Basketball League (ABL) in 1996, and the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) in 1997. The ABL unfortunately folded after just two years, and the WNBA has led women’s basketball in the US ever since.

We’re now getting into the part of women’s basketball history where there are so many accomplished Black women that it’s hard to choose who to talk about, but I do want to expand briefly on two members of the 1996 team who became legendary WNBA players.

Lisa Leslie, after an enormously successful high school and college career, played for the Los Angeles Sparks from 1997 to 2009, winning two WNBA championships, three WNBA Most Valuable Player (MVP) titles, and two Defensive Player of the Year titles. She was the first player to record a double-double in WNBA history, as well the first ever to dunk in a WNBA game. She set scoring records throughout her tenure, ultimately becoming the first to reach 6,000 career points in 2009, the year she retired. She remains the fourth-highest rebounding leader in WNBA history. In 2011, she was honored as one of the top fifteen players in the history of the WNBA, alongside her 1996 teammate Sheryl Swoopes.

Sheryl Swoopes was the first player to be signed in the WNBA, and for good reason. After setting records throughout high school and college – including scoring 47 points in the 1993 NCAA championship game, a record for most points in a title match that no one in women’s or men’s basketball has beaten – and, of course, becoming an Olympian, Swoopes went on to win the first four WNBA championships with the Houston Comets, become the first three-time WNBA MVP and Defensive Player of the Year, and record the first triple-doubles in both the regular season and the playoffs. She was also the first women’s basketball player to have a Nike shoe, the “Air Swoopes”. And in 2005, she set another record – becoming the first Black American athlete active in a major team sport to come out in the media.

2000s-2010s: Getting to out and proud

Black queer athletes have no doubt been a part of women’s basketball since its inception but have had to hide their sexualities in public – a trend that still characterized the first decades of the WNBA. League leadership sought to put forward an image of “family-friendliness”, one that required their players to present as feminine and heterosexual, often centering media attention on players with husbands or children.

This was part of why Swoopes’s 2005 announcement that she was in a relationship with a woman caused a stir: Swoopes was the league’s superstar and had previously been part of the WNBA’s heteronormative marketing while she was still married to a man. Swoopes, in an interview with The Advocate, also talked about the intersections of Blackness and queerness: “You have your Rosie O’Donnells, your Ellen DeGenereses… and I was trying to figure out what gay African-American woman has come out and can represent the gay African-American community. And I can’t really think of one.”

Swoopes herself became that woman for many other Black WNBA legends who followed not long after. Seimone Augustus, an eight-time All-Star and 2011 finals MVP who led the Minnesota Lynx to four WNBA championships, publicly came out in 2012 when she married her partner of five years. The next year, Brittney Griner, who wanted to be open about being a butch lesbian while playing at Baylor University but faced pressure from her white coach (the infamous Kim Mulkey, now head coach at LSU) to hide it, was the number one draft pick in the WNBA, and used her platform to speak publicly about facing racist, homophobic, and misogynistic abuse throughout her life.

Two-time Olympic medalist and five-time WNBA All Star Angel McCoughtry came out on Instagram in 2015, naming the homophobia she’s faced along the way. Candace Parker, another one of the best players of all time, who won two WNBA MVP titles (one of them while she was a rookie, making her the only one in the W ever to win MVP and Rookie of the Year in the same season), two WNBA championships, and was named to seven WNBA All-Star teams, and whose versatility changed what it looked like to play a forward and center in women’s basketball, revealed in 2021 that she had married a woman two years prior. These Black queer players and others helped to shift the WNBA from a league that stifled queerness and transness to one of the most welcoming professional sports leagues in the US – though there’s still, of course, a lot of anti-Black homophobia to defeat.

2020s: The current state of American women’s basketball

The WNBA is one of the hardest leagues in the world to make it into. With currently only twelve teams and twelve roster spots on each team, that’s a maximum of 144 spots – and due to salary caps, not every team even fills their roster, so the actual number of players is usually in the 130s. That means last year, draft-eligible NCAA women’s basketball players had only a 0.9% chance of actually playing in the WNBA.

Despite those incredibly difficult odds, Black women still dominate the league. In 2023, 63.8% of WNBA players were Black, 19.1% were white, 10.6% were listed as “two or more races”, 1.4% were Latinx, and 1.4% were Asian, while 3.5% did not list their race. And it’s not just the sheer numbers. Black women led the game in the vast majority of the major single-season statistics last year – many of whom also set all-time records within a single season for doing so, like A’ja Wilson for field goals and 2-point field goals, Alyssa Thomas for assists and defensive rebounds, and Jewell Loyd for scoring and free throws.

Despite these records, the league’s most coveted award went to a white player, Breanna Stewart, in a highly-controversial 2023 MVP race that I’ll talk more about in future posts. But Black players won all the other major postseason athlete awards, including A’ja Wilson, who won both Finals MVP and Defensive Player of the Year; Aliyah Boston, who won Rookie of the Year by a unanimous vote; Satou Sabally, who won Most Improved Player; Alysha Clark, who won Sixth Player of the Year; and Elizabeth Williams, who won the Kim Perrot Sportsmanship Award. The 2023 WNBA All-Star roster – which is voted on by fans, WNBA players, and sports media, and then narrowed down by coaches – showed that Black players are not only accomplished but popular: 78% of the players chosen were Black. We don’t have these stats or awards for the ongoing 2024 season yet, of course, but Black players continue to lead the league: A’ja Wilson is widely considered to be the best player in the world, while players like Jackie Young, Napheesa Collier, Alyssa Thomas, Jonquel Jones, Arike Ogunbowale, Kahleah Copper, and Kayla McBride are also having explosive seasons.

Alyssa Thomas, Jewell Loyd, Jonquel Jones, Kahleah Copper, Arike Ogunbowale, and Kayla McBride have something else in common: they’re all out as queer as well. In fact, 76% of the out queer players currently active in the league are Black, including other leaders like the aforementioned Brittney Griner; Layshia Clarendon, the first out nonbinary athlete in the WNBA; DeWanna Bonner, who is engaged to her teammate Alyssa Thomas, and just recently passed her ex-wife Candice Dupree to become fifth all-time in career points; Chelsea Gray, the “Point Gawd” of the Las Vegas Aces; Natasha Cloud, one of the biggest social activists in the league; and many, many more. In fact, there are so many out Black stars that not only is two-thirds of this year’s US women’s Olympic roster made up of Black players, but half of those Black players are openly queer as well.

So why, in a league dominated by Black women, including a huge number of out queer players, with a long legacy of Black leadership, is there so much attention right now on a straight white rookie? Because of the other forces that Black athletes have to fight against in their efforts to succeed: misogynoir and the specific intersection of anti-Black racism and homophobia in American women’s basketball, which I’ll delve into next time.

Mutual Aid Request

Help support three different humanitarian initiatives on the ground in Sudan, working to alleviate the suffering of people during genocide: the Basmat Wasal initiative and Sameh Makki’s kitchen appeal, both of which are providing food, and an initiative to get medical supplies for the Northern State hospital. Donate here to help all of these initiatives.