Delving into the Caitlin Clark discourse

A fun announcement: my friend Cameron Michels and I wrote a paper recently, and it got accepted by an academic journal! The paper is called “‘Pass it to your girlfriend!’: A collaborative autoethnography of a friendship through women’s sports fandom”, and in it we discuss our feelings as fans who are critical of racism, misogyny, and homophobia in women’s basketball and soccer in the United States.

It was a perfect topic us to collaborate on because Cameron is a critical feminist sports scholar currently pursuing her doctorate, I’ve published a couple fan studies articles in the past, and we got into women’s basketball together. Our paper will be out next March in a special issue of Transformative Works & Cultures that is focused on sports fandoms, and I’ll definitely be linking to that when it’s available.

Our paper is also incredibly relevant to today’s topic! This is the second in my series on how Black leadership is central to the WNBA. I’ve been avoiding writing this particular post because every time new Caitlin Clark discourse comes up, I get more and more annoyed that I even have to think about it. But the WNBA’s month-long break for the Olympics helped give me a little space to get my thoughts together without constantly bursting from anger…even though I didn’t manage to get this post out until the day the WNBA is back in session, oops!

So today we’re talking about the glorification of whiteness in women’s basketball in the US and the way it contributes to anti-Black racism, using examples of recent events around Caitlin Clark to illustrate larger patterns. The concept of misogynoir, which was developed by cultural studies scholar Moya Bailey, is key to this analysis. Misogynoir is the specific intersection of anti-Blackness and misogyny that Black women face, and focuses in particular on depictions of Black women in media – which is all too relevant for Black women’s basketball players.

But first, a couple requests.

Mutual Aid Request

Today’s mutual aid request is for S, a friend of my dear friend TK. S is living in a horrific abusive housing situation and has overextended themselves to try and make rent, to the detriment of their own health while they are already disabled. They are three-quarters of the way to a goal of $6,000 that will help them get out of their lease, fix their car, and secure new housing to escape their current situation. You can donate to S’s GoFundMe, or send money to TK with the note “For S” on Venmo, CashApp at $torkz428, or Paypal at torkz.

Activism Request

I’ve decided to add an activism request along with my mutual aid request for each newsletter! Today’s activism request, if you live in the United States, is to send an email to your representative and senators asking them to keep funding the CDC’s program for COVID vaccines for uninsured adults. Existing funding for this purpose ends this month. There are template emails available, but letters to elected officials are most effective when they start with a brief personal comment (a sentence or two) about why vaccine access for uninsured people matters to you, your loved ones, and your community. Here’s where you can send your email on renewed COVID vaccination funding for uninsured adults!

I have four main points that I want to cover here about whiteness and misogynoir in women’s basketball. They are:

White players get promoted and treated better within leagues, media, and fan bases than Black players

Black players receive more racist treatment in these same areas, including being undervalued, facing harassment, and being subjected to unfair double standards

Homophobia and transphobia exacerbate these power imbalances

Non-Black players need to do more to fight racism

And all of this is happening while Black players lead the WNBA in every way. As a reminder, in 2023, 63.8% of WNBA players were Black, 19.1% were white, 10.6% were listed as “two or more races”, 1.4% were Latinx, and 1.4% were Asian, while 3.5% did not list their race. Beyond the sheer numbers, Black women led the game in the vast majority of the major single-season statistics last year – as they have most seasons. I discussed this more in my last post on the history of Black women’s leadership in basketball, but it’s necessary context for today as well.

So let’s dig into it.

White women’s basketball players get promoted and treated better…

Caitlin Clark is not the first white basketball player to be designated the “Great White Hope” who will “save” women’s basketball. When the WNBA was first founded, it was Rebecca Lobo; in the next era of the league, it was Sue Bird. In 2020, it was Sabrina Ionescu. And now, it’s Caitlin Clark.

The WNBA is complicit in this disproportionate promotion of white athletes. As I mentioned in my last post, the league’s desire to court straight white male fans led to them shaping the image of the WNBA around white, (presumed) straight, feminine women – what sports sociologist Mary G. McDonald refers to as the “good white girl” construct – as well as promoting an image of “family-friendliness” that would encourage fathers to bring their daughters to games.

But it’s not just the league. White players also get far more positive media attention, regardless of their skill or accomplishments. In 2020 (when the proportion of Black players was actually even higher), sports management scholars Risa F. Isard and E. Nicole Melton looked at the number of media mentions that WNBA players received in online articles from ESPN, CBS Sports, and Sport Illustrated, and they found that even when controlling for factors like number of points or rebounds by a player, Black WNBA players receive less than half as much media coverage as white players, despite white players making up less than 20% of the league.

To give an example, Sabrina Ionescu, who is white and was a rookie in 2020, but only played only three games that year before a season-ending injury, received twice as much media coverage as A’ja Wilson, the 2020 MVP, who is Black. And this came during a season that WNBA players had dedicated to Black Lives Matter and protesting the murder of Breonna Taylor, which makes the media disparity even more glaring.

The media bias also impacts the WNBA’s yearly awards, which are voted on by a panel of sportswriters and broadcasters. The 2023 MVP race was the closest in WNBA history, with three players leading the way: Connecticut Sun’s Alyssa Thomas, Las Vegas Aces’ A’ja Wilson, and New York Liberty’s Breanna Stewart. Despite the fact that Alyssa Thomas, who is Black, had an unprecedented season where she averaged nearly a triple-double (she is also the record-holder in triple doubles across WNBA history, and by a lot), and despite the fact that she received the most first place votes for MVP, she did not win; neither did A’ja Wilson, who is widely considered the best player in the league, but was dealt the indignity of one voter putting her in fourth place, bringing down her overall score. Instead, Breanna Stewart, who is white, took home the MVP title for the second time because she had more second-place votes than Thomas.

And then there’s endorsements and sponsorships. Caitlin Clark secured a deal with Nike for a signature shoe before she had even played her first WNBA game, while A’ja Wilson, already a two-time WNBA MVP, five-time All-Star, two-time WNBA champion, and Olympic medalist, didn’t have her Nike signature shoe announced until a month after Clark’s. In fact, before Wilson’s deal was announced, the last four WNBA players to have a signature shoe were all white, and there hadn’t been a new signature shoe for a Black player since Candace Parker’s two Adidas shoes in 2010-2011.

…while Black players face racism through harassment, unwarranted criticism, and double standards

Sports media traffics in the worst kinds of misogynoiristic tropes when it comes to Black women’s basketball players. Just within my own memory, from Don Imus’s racist comments about the Rutgers women’s basketball team in 2007, to the backlash that Angel Reese received in 2023 for making a trash-talking gesture at Caitlin Clark during the NCAA championship finals (a gesture Clark had often made herself), I can easily trace a history of misogynoir in media and public discourse about women’s basketball.

Those dynamics have been made even clearer this season when it comes to the double standards in how Clark is portrayed compared to Black players – and particularly when it comes to Black players who have any kind of interaction with Clark that they can be criticized for. Black players are depicted as “jealous” of Clark’s success, or as being particularly confrontational towards her on the court, playing into nasty racist stereotypes about white women needing to be “protected” from aggressive Black women.

Let’s take the case of players fouling Clark, which her fans have claimed she faces disproportionately compared to other rookies. If you look at this season’s stats so far, it’s true that Clark is the rookie drawing the highest rate of fouls per game, in part because she’s identified by opposing teams as a strong player – but also because she’s the rookie playing the most minutes, and by far. If you instead look at fouls drawn per minute played for the five rookies who’ve played the most minutes overall, Aaliyah Edwards of the Washington Mystics is drawing a higher rate of fouls at almost 0.16 fouls per minute played, while Angel Reese is very close to Clark at around 0.12 fouls per minute played. Yet I’ve not heard anyone saying that Edwards, who is Black, is being treated unfairly.

Or let’s look at the specific case of Chennedy Carter’s well-publicized foul against Caitlin Clark. In June, Carter, who is Black and plays for the Chicago Sky, hip-checked Clark in an off-the-ball foul that was later upgraded to a flagrant 1 foul. Outrage exploded across the country; the Chicago Tribune editorial board called the foul an “assault”, and Carter was harassed for it outside a hotel in Washington D.C. where Sky players were staying. However, another instance of a veteran committing a hard foul on a rookie just a week earlier got far less attention: Connecticut’s Alyssa Thomas was ejected from a game after a flagrant 2 foul on Angel Reese. Both Thomas and Reese are Black, and Thomas’s foul did not cause the same kind of public eruption in mainstream media.

To be clear, I do not mean to say that Thomas should be subjected to the same racist treatment as Carter was – no one should! Basketball is a physical sport, and while safety is important, the racist backlash to Carter’s foul had nothing to do with actual player safety.

Homophobia and transphobia exacerbate these power imbalances

Then there’s the homophobia and transphobia of it all. As Frankie de la Cretaz writes for Andscape:

“Earlier this month, conservative sports pundit Clay Travis claimed the Fever star was a victim of discrimination against ‘white heterosexual women in a Black lesbian league’ after Clark received a flagrant foul 1 from Sky guard Chennedy Carter.

With that statement, Travis said the quiet part out loud. Pitting Clark, a white, heterosexual woman who fits into conventionally approved, Eurocentric standards of womanhood, against the rest of the league, which is predominantly Black and perceived as largely queer or gender non-conforming, reinforces long-standing tropes of the queer villain.”

And make no mistake, this is a racialized queer villain. While the WNBA’s early years were founded in heteronormativity, the league’s evolution over the years has included folding white cisgender queer women into the image of the ideal hooper. White gay players like Breanna Stewart, who is also married with a kid, are even featured in ads that make it clear that the league’s “family-friendliness” narrative has now changed include some queer people, especially when those narratives still align with heteronormative structures.

But Black queer and trans players do not benefit the same way from this shift. Isard and Melton’s research on the 2020 season also found that Black players with masculine gender expression received less media attention than other Black players, while white players who presented masculine received more mentions than other white players! New York Liberty star Jonquel Jones has talked about this herself – despite being one of the best players in the league and the 2021 MVP, she believes that being Black, openly gay, and presenting masculine have cost her endorsements.

And it’s not just the disparity in coverage. The way that Black queer basketball players are depicted is steeped in misogynoir, homophobia, and transphobia. Gender studies scholar Kendall Nichelle Rallins, who is currently a PhD student at UC Santa Barbara, dedicated her 2022 M.A. thesis to this topic, looking at the way Black queer WNBA players are depicted and represent themselves in both mainstream media and social media. (I highly recommend reading Rallins’s thesis in full if you can because it is excellent.)

Rallins looks at the ways that ideologies of misogynoir, homophobia, transphobia, and fatphobia contribute to how Black queer players are seen:

“Black queer WNBA players experience a simultaneous invisibility and hypervisibility within mainstream media, as direct results of misogynoir and an enforcement of heteronormativity. Generally, there is a silence around Black players that erases their contributions and presence within the WNBA. When they are mentioned, they are frequently portrayed in racist and misogynistic ways that depict them as aggressive, combative, and able to endure higher levels of pain. Black queer players are most frequently the target of these narratives, especially if they are masculine-presenting or dark skin women.” (p. 76)

She cites examples where Black players like Liz Cambage, Courtney Williams, and Brittney Griner have been framed as threatening or predatory simply for things like their size (supposedly a good quality in basketball!), masculine presentation (or even assumed masculine presentation), or because they had confrontations with white people. It’s not hard to trace the parallels with how Chennedy Carter and Angel Reese have been framed as antagonists to Caitlin Clark this season.

Black queer players resist these narratives by speaking out and representing themselves, both through social media and by cultivating relationships with journalists who have integrity and are dedicated to reporting on women’s basketball, unlike sports reporters from mainstream outlets that only cover the WNBA during key moments. Rallins discusses how Jonquel Jones, Courtney Williams, and Natasha Cloud have used their platforms to speak out about the discrimination they face, their refusal to code-switch or change themselves just to gain popularity, and their own commitment to fighting for racial justice, and how their words are uplifted by journalists like Ari Chambers, whose positionality as a Black woman herself leads her to tell athletes’ stories with respect and care.

However, it cannot only be Black players and journalists who speak up about anti-Blackness and misogynoir. Non-Black leaders in women’s basketball, particularly white folks, have a responsibility here as well.

Non-Black players need to do more to fight racism in women’s basketball

I’ve seen Caitlin Clark play once in person. In spring 2023, the first rounds of the NCAA women’s basketball tournaments were split between Greenville, South Carolina and Seattle, Washington, where I live. My friend Cameron and I went to a bunch of the games, including the Elite Eight game between the Iowa Hawkeyes and the Louisville Cardinals.

We’d heard of Clark at that point, but she wasn’t close to as famous as she is now. Still, there was a noticeable difference in the stadium between the previous match we’d watched and the Iowa game. The crowd felt like it was 90% white Iowa fans, and throughout the game, they were so intense that, for the first time I’ve ever experienced at a sports game, I actually felt unsafe being a person of color sitting there who wasn’t cheering for their team.

So it’s not at all a surprise to me that Clark’s fans have been spewing racist, anti-Black nonsense in response to perceived slights to their star. But Clark’s own responses to it have also been vastly insufficient.

In June, Jim Trotter, a reporter for The Athletic, one of the prominent sources for women’s basketball news in the US, asked Clark if she was bothered by her name being used to further culture wars. Clark’s initial answer was, “No, I don’t see it.”

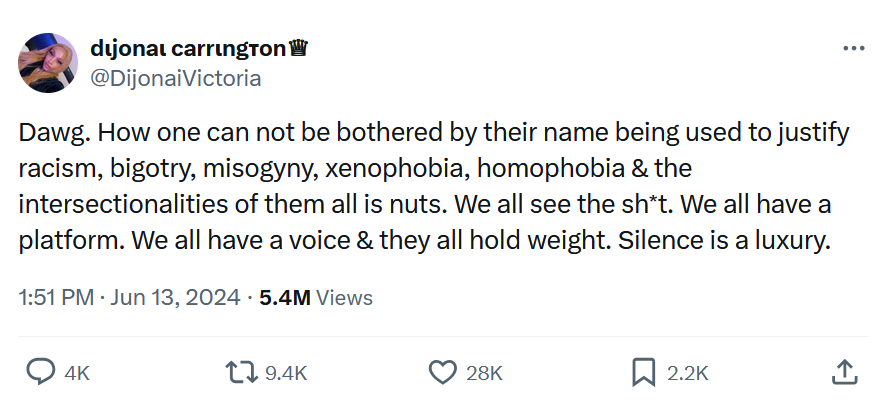

In response, DiJonai Carrington, a guard for the Connecticut Sun who is Black and queer, called out on her Twitter how ridiculous Clark’s answer was:

Clark then backtracked a few hours later, responding to a reporter who asked her about racism and misogyny by saying:

“People should not be using my name to push those agendas. It’s disappointing. … Everybody in our world deserves the same amount of respect. The women in our league deserve the same amount of respect.”

That’s still too weak an answer for me. Clark owes her entire ability to be a professional basketball player to the Black women, many of them queer, who have made this game what it is in the US. The very least she can do is to condemn bigotry that is perpetuated in her name beyond just calling it “disappointing”, and uplift Black women specifically as being harmed by racism, particularly when Black players like Chennedy Carter and Angel Reese are demonized because of what they’ve supposedly done to Clark.

Clark being a rookie is also not an excuse. Paige Bueckers, a white player at UConn who is widely predicted to be the #1 WNBA draft pick in 2025, was named the best college athlete in women’s sports at the ESPY Awards in 2021, when she was only a freshman. A nineteen-year-old Bueckers used her acceptance speech to call out the disparity in coverage for Black women:

“With the light that I have now as a White woman who leads a Black-led sport and celebrated here, I want to shed a light on Black women. They don’t get the media coverage that they deserve. They’ve given so much to the sport, the community and society as a whole and their value is undeniable. I think it’s time for change.

Sports media holds the key to storylines. Sports media and sponsors tell us who is valuable, and you have told the world that I mattered today, and everyone who voted, thank you. But I think we should use this power together to also celebrate Black women.”

Clark and Bueckers are the same age – now twenty-two – and Bueckers was famous nationally even before Clark was. And what Bueckers said is still, in my opinion, the bare minimum.

It’s not too much to ask that white players whose popularity is founded in part on their whiteness use that privilege to actively fight against anti-Blackness, especially in a league like the WNBA where fighting racial injustice has become a key part of many players’ work. Black players rightfully lead there as well, of course, which I will talk more about next week – but non-Black players, journalists, and prominent voices in women’s basketball need to show up better as allies, especially when they are being given platforms that Black players are denied.