Five queer Palestinian short films deserve justice and liberation

This week, I am recommending short films created by or about queer Palestinians. And I wish it were a given that I could write this week’s newsletter without first having to explain why it’s necessary to support Palestinian liberation. But I’m seeing some of the worst misinformation and suppression of pro-Palestinian speech, and the worst dehumanization of Palestinian people, than I have seen in my entire life.

If you already feel unequivocal in your support for Palestine, feel free to skip right down to the next section. But if you are conflicted about supporting Palestinians because you are hearing in the news, or from your friends and family, that they are inflicting disproportionate violence on Israeli civilians, here are some things to consider.

Consider the structural violence that Palestinians have been under for decades under the Israeli apartheid state. Consider the unlivable conditions in occupied Gaza, an area almost exactly the size of my hometown of Seattle in the U.S., but with 2.3 million people, 53% of whom live below the poverty line. Consider that 47% of the population of Gaza are under the age of 18, and that 80% of Gazan children and youth live with depression, fear, and PTSD. Consider that Israel controls everything that goes in and out of Gaza – people, food, energy, water, medical supplies. Consider that in response to the current uprising, Israel has blockaded all of those resources, which is an unequivocal war crime.

Consider that direct violence from conflict has also been hugely skewed towards killing Palestinians. Consider that from 2008 to September 2023, there were 6,407 Palestinians killed by Israel – compared to 308 Israelis, which is less than 5% of the Palestinian deaths. Consider that 22.4% of those Palestinian deaths were children – a total of 1,437 murdered, almost five times as many as all the Israelis killed. Consider that Israel has over 5,200 Palestinians in prison, including 170 children who can face up to twenty years for throwing rocks at Israeli soldiers. Consider that more than 1,200 of those prisoners are being held without trial, or in some cases without even being charged. Consider that there are two systems of law in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, where Palestinians are tried under military law and Israelis under civilian law for the exact same crimes – a system of such profound injustice that it was not even present under South African apartheid.

Consider that the Israeli government, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in particular, encouraged the growth of Hamas in an effort to sow division between Hamas-controlled Gaza and the Fatah-controlled West Bank. Consider that Israel and its western allies have decried all forms of nonviolent resistance to Israeli apartheid, including the Boycott, Divest, and Sanctions (BDS) movement, as antisemitic. Consider that in 2018-2019, when Palestinians protested peacefully at the Gaza-Israel border every Friday in the Great March of Return for almost two years, Israeli soldiers targeted them with live bullets and tear gas, killing 214 and injuring over 36,000 Palestinians, including nearly 8,800 children.

Consider that Israel dropped over 6,000 bombs on Gaza in the first six days of their genocidal response to the current Palestinian freedom fight. Consider that Israel is also using chemical warfare like white phosphorus against civilians. Consider that the Israeli government is distributing 10,000 rifles to illegal Israeli settlers in the West Bank, despite the West Bank not being a Hamas stronghold, to kill Palestinian civilians.

Consider the rampant misinformation and media bias in the mainstream media across the world. Consider that media outlets have had to issue retractions after misreporting that Hamas is using rape as a weapon of terror (which has no evidence), and that people have been circulating AI-generated fake images to claim that Hamas is beheading babies, an allegation that has not even been confirmed by the Israeli army. Consider that journalists are being fired or sidelined if they criticize the Israeli government or military, or even just if they are Muslim.

Consider – and this is important for my fellow queer and trans folks – the pinkwashing that the Israeli government engages in to frame Israel as the only “safe” place for queer people in southwest Asia, not only invoking racist and Orientalist stereotypes about Arab cultures, but also invisibilizing the violence Israel perpetrates on queer Palestinians. Consider that Israel uses pinkwashing to project a better image around the world, including in my hometown of Seattle in the United States when, in 2012, local queer Palestinian activists and allies exposed the propaganda of a pinkwashing Israeli tour.

If those considerations are not sufficient for your support and empathy for Palestinian liberation, then please unsubscribe from my newsletter.

In addition to finding short films created by or about queer Palestinians for this week’s newsletter, I was excited to discover Queer Cinema for Palestine, which is both a global film festival and a pledge for filmmakers. The festival runs in cities all over the world as well as virtually, and includes but is not limited to films by Palestinians; their next festival is coming up from November 29 through December 10, 2023, and you can sign up here for updates as tickets and screenings become available. The pledge is for filmmakers, film artists, and production companies committed to LGBTQIA+ liberation who stand in solidarity with Palestine and agree to boycott the Israeli-government sponsored LGBT film festival TLVFest, and you can see the list of over two hundred signatories across the world here.

And along with watching this week’s films, please do what you can to fight for Palestinian freedom:

I have not found pronouns explicitly listed for any of the film creators or characters, so I have not listed them myself, but in my descriptions have used pronouns that others have used to refer to them, or just their names.

“When a person saw his neighbor leaving, he was afraid to stay, and left his house, all his stuff, his land, his grove – they left everything.”

Houria | حـ(و)ـرية, an experimental film directed by Raafat Hattab, intercuts between a violinist (Boodi El Esawi) playing on a beach at Manshiye who is joined unexpectedly by a mermaid (played by Raafat Hattab himself), a person getting their chest tattooed, and an interview with Hattab’s grandmother, Yousra, talking about her parents’ flight from their home in Jamaseen Al-Garbi when she was a baby, during the 1948 nakba (“catastrophe”), during which thousands of Palestinians were killed and an estimated 700,000 were displaced because of Israeli ethnic cleansing. The gender fluidity of Hattab’s mermaid, the permanence of the tattoo, and the impermanence of Palestinian life and homeland in Yousra’s story come together to illustrate the paradoxes and grief of dislocation that Palestinians face daily.

Creator Raafat Hattab is a queer Palestinian interdisciplinary artist who was born and raised in Jaffa. In 2018, his film was included in an exhibition called The Unmarked Body that began in Jerusalem and then traveled to the United Kingdom. Hattab’s artist page describes the film, telling us, “Interested in ‘the diversity in the middle’, Hattab dissolves binaries starting with that of male/female, inviting viewers to tread on the line between perceived genders. His film, Houria | حـ(و)ـرية, translated to mermaid in English and a play on the Arabic horia حرية meaning freedom, invokes The Little Mermaid, who traded her vocal chords for legs, taking silence to become human. While Hattab’s Houria | حـ(و)ـرية locates freedom in the sexless mermaid, whose human anatomy is truncated from the waist down, his ‘Bride of Palestine’ alter ego uses gender as a tool to problematize political oppression.”

Houria | حـ(و)ـرية

“Aren’t you going to tell him already?”

Living Alone Without Me | عايشة مع وحدة, بلاااي, created by Eli Rezik, uses its short runtime to tell a clear and powerful story. A man filming a video diary tells us that he is planning to propose to his girlfriend Hanin after five years together. Though he is foregrounded in the shot, his voice is cut off shortly into the film, and we instead hear the conversation betweeen Hanin and another woman sitting far behind him, out of focus. With the plaintive sounds of the Mashrou’ Leila song “Fasateen” in the background (I recommended a short film featuring the Lebanese band Mashrou’ Leila earlier this year), we learn more about the women’s relationship even as we never see their faces clearly, evocative of the way they have had to hide in plain sight.

Living Alone Without Me | عايشة مع وحدة, بلاااي

“Am I so desperate to take out your dead body, to drag you out of the closet or the grave?”

Dawoud, Ya Yonathai | داود، يا يوناثاي, directed by Qais Assali, takes us into the archive of Arab literature, and in particular the diaries of Palestinian educator and Arab nationalist Khalil Al Sakakini and the way he speaks about his “soulmate” Dawoud Al Sidawi. Through animation, research, and live performance, we hear Al Sakikini’s sorrow about the loss of the person that he framed as the “David” to his Jonathan, even while director Qais Assali asks us to sit with the discomfort of attempting to read meaning into the private writings of a long-dead person. The experimental film is not always easy to understand: it opens with a description of all the things the film is not, the animation of real photographs to mimic people speaking feels strange and gets us into uncanny valley territory, and portions of the speech appear to deliberately not be subtitled in English. But these difficulties are not unintentional; rather, they are a profound part of the messiness of queer histories and how we retell them.

Creator Qais Assali is a Palestinian interdisciplinary artist who was born in Palestine and raised in the United Arab Emirates before returning to Palestine as a teenager, later studying and teaching art and communication at a number of different universities in the United States and Palestine. “I seek to complicate historical hierarchies,” Assali says in their artist’s statement. “I am the result of my generation, experiencing the entire Second Intifada and trying to frame or shape it differently. These historical narratives fuel my passionate gaze toward the Middle East by subverting notions of oppression and victimhood. My work shows how the case of Palestine is more broadly connected to the problems of the Arab world and the whole world and to see the historic Palestinian relationship to colonization and imperialism.”

Dawoud, Ya Yonathai | داود، يا يوناثاي

“Is that the new style in town? Or do you miss the good old days at the checkpoints?”

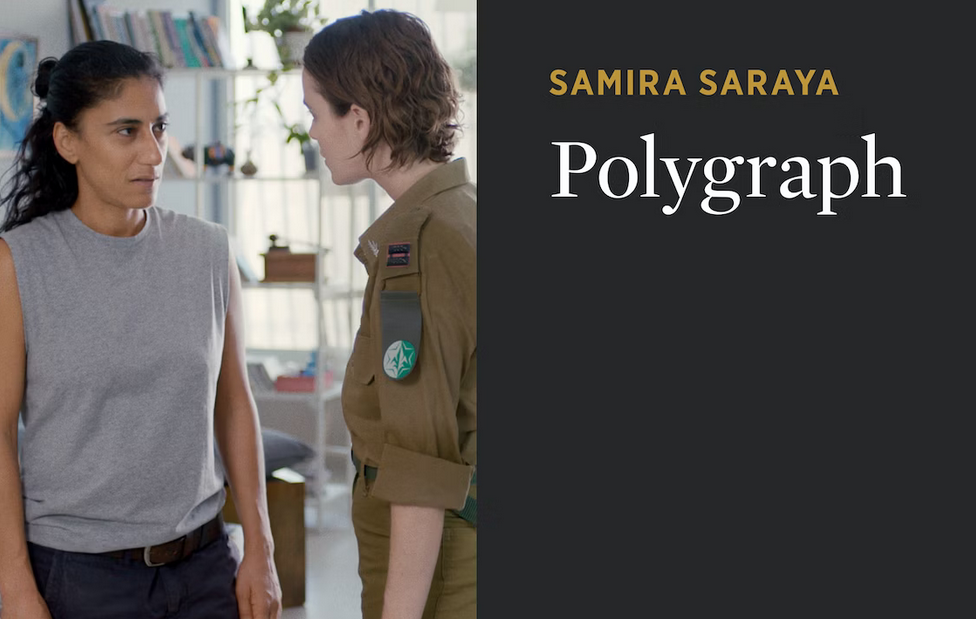

Polygraph | بوليجراف, written and directed by Samira Saraya, never lets you forget about the inherently unequal power dynamic between Yasmine (played by Saraya herself), a Palestinian Arab nurse living in Tel Aviv, and her Israeli lover Or (Hadas Yaron), who is an intelligence officer in the Israeli army – nor about the way that Yasmine’s life is surrounded by Israeli occupation and suppression, even just when driving her girlfriend to work. When Yasmine’s sister Jehan (Fidaa Zidan) comes to visit from the occupied West Bank, the dinner party Yasmine hosts to introduce them becomes a site of tension around Or’s participation in upholding Israeli apartheid.

Creator and star Samira Saraya, a queer Israeli-Palestinian who grew up in Tel Aviv and worked as a nurse herself before becoming an actor and filmmaker, drew from personal experience with a past partner in creating the film. “I think for me, dealing with this story, I was dealing with my emotional and psychological situation when I was inside this relationship. I was understanding, after we separated, that a really large part of me wasn’t — I don’t want to say existing — but wasn’t present,” Saraya said in an interview with Met Radio. “I even made it invisible to myself. It was only later that I realized I wanted to deal with it in a cinematic way, as well as making it a platform to discuss not only my personal story, but also to take it to wider questions about our society. The Israeli, the Jewish and the Arab society. Can they exist in a relationship when the practice of the Israeli society is militaristic?”

Saraya also names the perplexing and disturbing experience of growing up in Israel as a Palestinian. “Even just running on the beach, when I run by the Jaffa Museum, where it’s this house; the leftovers of a neighbourhood of thousands of people living here and it was vanquished, and they only left one house and made it a museum for the celebration of freeing Jaffa. So this whole sphere is so violent and erases me by existing, without even doing anything active. Like in the boulevard, a boulevard named after a guy asking for transfer for the Palestinians. So many things are wrapping around us, and it’s not visible, you know? People do not understand what it means to walk in the streets of Israel for us Palestinians, and they don’t talk about it. I thought I wanted to, in this short film, bring in from the outside, images of Yasmine just driving in the streets of Tel Aviv.”

Polygraph | بوليجراف

“As a Palestinian growing up in Jerusalem, the best way to get by is to have a coping mechanism. I was that kid at school who was into strange songs and odd singers.”

I’ve recommended Wifi Rider | راكب إنترنت, directed by Roxy Rezvany, to you before, but it’s absolutely worth watching again. The documentary short introduces us to Shukri Lawrence, a young, queer Palestinian-Armenian fashion designer and photographer. Shukri, who was born in East Jerusalem and now lives in Jordan, came to fame through his Instagram account @wifirider, which he created as a teenager to share his style, fashion, and takes on pop culture. The film, shot on 16mm, also integrates footage from Shukri’s early life as well, with Shukri’s voiceover to tell us about his story and the clothing label named Trashy Clothing that he founded with his co-designer Omar Braika, who is also Palestinian.

The displacement and threat of state violence that Shukri faces is felt throughout the docu-short; he begins by telling us how as a child he dreamed of moving to France, where he thought he would find freedom from his experience in Israel. However, over the course of his adolescence, Shukri began to understand that while he, like all Palestinians currently, has no real home, he prefers his life to still be grounded in the Arab world where he still has community in the Palestinian diaspora.

“Shooting on film for a story like this was about showing audiences the colour, texture and sensitivity through which Shukri sees the world,” said director Roxy Rezvany to Short of the Week. “I feel that there’s a tendency with films about ‘youth and the internet’ to wed those stories to a digital aesthetic, but I think that would have belied the real intensity of Shukri’s emotions and the fact this is much more than a story about social media. It was also about contrasting our imagery with the types of portrayals that Shukri had seen of Arab men, women and cities that fuel the negative stereotypes, and the photojournalistic coverage of ‘the Middle East’ that we see emerge through coverage of war and occupation that only shows Palestinians traumatised.”

Wifi Rider | راكب إنترنت